Scientists shed light on inner workings of human embryonic stem cells

Thursday, 30 April 2009

Scientists at UC Santa Barbara have made a significant discovery in understanding the way human embryonic stem cells function.

They explain nature's way of controlling whether these cells will renew, or will transform to become part of an ear, a liver, or any other part of the human body. The study is reported in the May 1 issue of the journal Cell.

The scientists say the finding bodes well for cancer research, since tumour stem cells are the engines responsible for the growth of tumours. The discovery is also expected to help with other diseases and injuries. The study describes nature's negative feedback loop in cell biology.

Because there is typically less "wiggle room" in the levels of microRNA compared to mRNA, further studies are needed to quantify more precisely the copy numbers of miR-145 and its targets, to figure out exactly how this layer of control really works, Kosik said.

The findings in embryonic stem cells might also have importance for cancer.

"There are sets of microRNA that are widely up- or down regulated in cancers," he said, noting that several studies have specifically linked low miR-145 levels to various forms of cancer.

"Tumour stem cells are the engines of tumours. If miR-145 is sustaining or maintaining a differentiated state, loss of that may have something to do with malignant transformation."

"We have found an element in the cell that controls 'pluripotency,' that is the ability of the human embryonic stem cell to differentiate or become almost any cell in the body," said senior author Kenneth S. Kosik, professor in the Department of Molecular, Cellular & Developmental Biology. Kosik is also co-director and Harriman Chair in Neuroscience Research of UCSB's Neuroscience Research Institute.

"The beauty and elegance of stem cells is that they have these dual properties," said Kosik.

"On the one hand, they can proliferate –– they can divide and renew. On the other hand, they can also transform themselves into any tissue in the body, any type of cell in the body."

The research team includes James Thomson, who provided an important proof to the research effort. Thomson, an adjunct professor at UCSB, is considered the "father of human embryonic stem cell biology." Thomson pioneered work in the isolation and culture of non-human primate and human embryonic stem cells. These cells provide researchers with unprecedented access to the cellular components of the human body, with applications in basic research, drug discovery, and transplantation medicine.

With regard to human embryonic stem cells, Kosik explained that for some time he and his team have been studying a set of control genes called microRNAs.

"To really understand microRNAs, the first step is to remember the central dogma of biology –– DNA is the template for RNA and RNA is translated to protein. But microRNAs stop at the RNA step and never go on to make a protein.”

"The heart of the matter is that before this paper, we knew if you want to maintain a pluripotent state and allow self-renewal of embryonic stem cells, you have to sustain levels of transcription factors, including Oct4, Sox2 and Klf4," said Kosik.

"We also knew that stem cells transition to a differentiated state when you decrease those factors. Now we know how that happens a little better."

Transcription factors are genes that control other genes. On the other hand, microRNAs are single-stranded RNA molecules that control the activity of other genes. When microRNAs in the genome are transcribed from DNA, they target complementary messenger RNAs (mRNAs), which serve as the templates for proteins, to either encourage their degradation or prevent their translation into functional proteins. In general, one gene can be repressed by multiple microRNAs and one microRNA can repress multiple genes, the researchers explained. In a wide variety of developmental processes, microRNAs fine tune or restrict cellular identities by targeting important transcription factors or key pathways.

Kosik's team found that levels of miR-145 change dramatically when human embryonic stem cells differentiate into other cell types. miR-145 was of particular interest because it had been predicted to target Oct4, Klf4 and Sox2. The new research shows that a microRNA –– a single-stranded RNA whose function is to decrease gene expression –– lowers the activity of three key ingredients, Oct4, Sox2 and Klf4, in the recipe for embryonic stem cells. The discovery may have implications for improving the efficiency of methods designed to reprogram differentiated cells into embryonic stem cell-like cells.

As few as three or four genes can make cells pluripotent. Those three factors are perhaps best known as three of four ingredients originally shown to transform adult human skin cells into "induced pluripotent stem cells" (iPS cells), which behave in nearly every respect like true embryonic stem cells. That four-ingredient recipe has since been pared down to one, Oct4, in the case of neural stem cells.

"We know what these genes are," Kosik said. That information was used recently for one of the most astounding breakthroughs of biology of the last couple of years –– the discovery of induced pluripotent skin cells.

"You can take a cell, a skin cell, or possibly any cell of the body, and revert it back to a stem cell," Kosik said.

"The way it's done, is that you take the transcription factors that are required for the pluripotent state, and you get them to express themselves in the skin cells; that's how you can restore the embryonic stem cell state. You clone a gene, you put it into what's called a vector, which means you put it into a little bit of housing that allows those genes to get into a cell, then you shoot them into a stem cell. Next, when those genes –– those very critical pluripotent cell genes –– get turned on, the skin cell starts to change; it goes back to the embryonic pluripotent stem cell state."

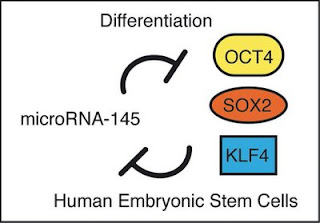

The researchers explained that a rise in miR-145 prevents human embryonic stem cells' self-renewal and lowers the activity of genes that lend stem cells the capacity to produce other cell types. It also sends the cells on a path toward differentiation. In contrast, when miR-145 is lost, the embryonic stem cells are prevented from differentiating as the concentrations of transcription factors rise.

They also show that the control between miR-145 and the "reprogramming factors" goes both ways. The promoter for miR-145 is bound and repressed by a transcription factor known as OCT4, they found.

"It's a beautiful double negative feedback loop," Kosik said.

"They control each other. That is the essence of this work."

"We have found an element in the cell that controls 'pluripotency,' that is the ability of the human embryonic stem cell to differentiate or become almost any cell in the body," said senior author Kenneth S. Kosik, professor in the Department of Molecular, Cellular & Developmental Biology. Kosik is also co-director and Harriman Chair in Neuroscience Research of UCSB's Neuroscience Research Institute.

"The beauty and elegance of stem cells is that they have these dual properties," said Kosik.

"On the one hand, they can proliferate –– they can divide and renew. On the other hand, they can also transform themselves into any tissue in the body, any type of cell in the body."

The research team includes James Thomson, who provided an important proof to the research effort. Thomson, an adjunct professor at UCSB, is considered the "father of human embryonic stem cell biology." Thomson pioneered work in the isolation and culture of non-human primate and human embryonic stem cells. These cells provide researchers with unprecedented access to the cellular components of the human body, with applications in basic research, drug discovery, and transplantation medicine.

With regard to human embryonic stem cells, Kosik explained that for some time he and his team have been studying a set of control genes called microRNAs.

"To really understand microRNAs, the first step is to remember the central dogma of biology –– DNA is the template for RNA and RNA is translated to protein. But microRNAs stop at the RNA step and never go on to make a protein.”

"The heart of the matter is that before this paper, we knew if you want to maintain a pluripotent state and allow self-renewal of embryonic stem cells, you have to sustain levels of transcription factors, including Oct4, Sox2 and Klf4," said Kosik.

"We also knew that stem cells transition to a differentiated state when you decrease those factors. Now we know how that happens a little better."

Transcription factors are genes that control other genes. On the other hand, microRNAs are single-stranded RNA molecules that control the activity of other genes. When microRNAs in the genome are transcribed from DNA, they target complementary messenger RNAs (mRNAs), which serve as the templates for proteins, to either encourage their degradation or prevent their translation into functional proteins. In general, one gene can be repressed by multiple microRNAs and one microRNA can repress multiple genes, the researchers explained. In a wide variety of developmental processes, microRNAs fine tune or restrict cellular identities by targeting important transcription factors or key pathways.

Kosik's team found that levels of miR-145 change dramatically when human embryonic stem cells differentiate into other cell types. miR-145 was of particular interest because it had been predicted to target Oct4, Klf4 and Sox2. The new research shows that a microRNA –– a single-stranded RNA whose function is to decrease gene expression –– lowers the activity of three key ingredients, Oct4, Sox2 and Klf4, in the recipe for embryonic stem cells. The discovery may have implications for improving the efficiency of methods designed to reprogram differentiated cells into embryonic stem cell-like cells.

As few as three or four genes can make cells pluripotent. Those three factors are perhaps best known as three of four ingredients originally shown to transform adult human skin cells into "induced pluripotent stem cells" (iPS cells), which behave in nearly every respect like true embryonic stem cells. That four-ingredient recipe has since been pared down to one, Oct4, in the case of neural stem cells.

"We know what these genes are," Kosik said. That information was used recently for one of the most astounding breakthroughs of biology of the last couple of years –– the discovery of induced pluripotent skin cells.

"You can take a cell, a skin cell, or possibly any cell of the body, and revert it back to a stem cell," Kosik said.

"The way it's done, is that you take the transcription factors that are required for the pluripotent state, and you get them to express themselves in the skin cells; that's how you can restore the embryonic stem cell state. You clone a gene, you put it into what's called a vector, which means you put it into a little bit of housing that allows those genes to get into a cell, then you shoot them into a stem cell. Next, when those genes –– those very critical pluripotent cell genes –– get turned on, the skin cell starts to change; it goes back to the embryonic pluripotent stem cell state."

The researchers explained that a rise in miR-145 prevents human embryonic stem cells' self-renewal and lowers the activity of genes that lend stem cells the capacity to produce other cell types. It also sends the cells on a path toward differentiation. In contrast, when miR-145 is lost, the embryonic stem cells are prevented from differentiating as the concentrations of transcription factors rise.

They also show that the control between miR-145 and the "reprogramming factors" goes both ways. The promoter for miR-145 is bound and repressed by a transcription factor known as OCT4, they found.

"It's a beautiful double negative feedback loop," Kosik said.

"They control each other. That is the essence of this work."

Human embryonic stem cells are poised between a proliferative state with the potential to become any cell in the body and a differentiated state with a more limited ability to proliferate. To maintain this delicate balance embryonic stem cells express a set of factors, including OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4, to control multiple genes that sustain the proliferative pluripotent state. A tiny RNA called miR-145 can repress these genes, and in turn, one of the transcription factors, OCT4, can repress miR-145. Thus, a double negative feedback loop sets the delicate balance.

Human embryonic stem cells are poised between a proliferative state with the potential to become any cell in the body and a differentiated state with a more limited ability to proliferate. To maintain this delicate balance embryonic stem cells express a set of factors, including OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4, to control multiple genes that sustain the proliferative pluripotent state. A tiny RNA called miR-145 can repress these genes, and in turn, one of the transcription factors, OCT4, can repress miR-145. Thus, a double negative feedback loop sets the delicate balance.

Kosik credits the lion's share of this discovery to first author

Kosik credits the lion's share of this discovery to first author

For more on stem cells and cloning, go to CellNEWS at http://cellnews-blog.blogspot.com/ and http://www.geocities.com/giantfideli/index.html